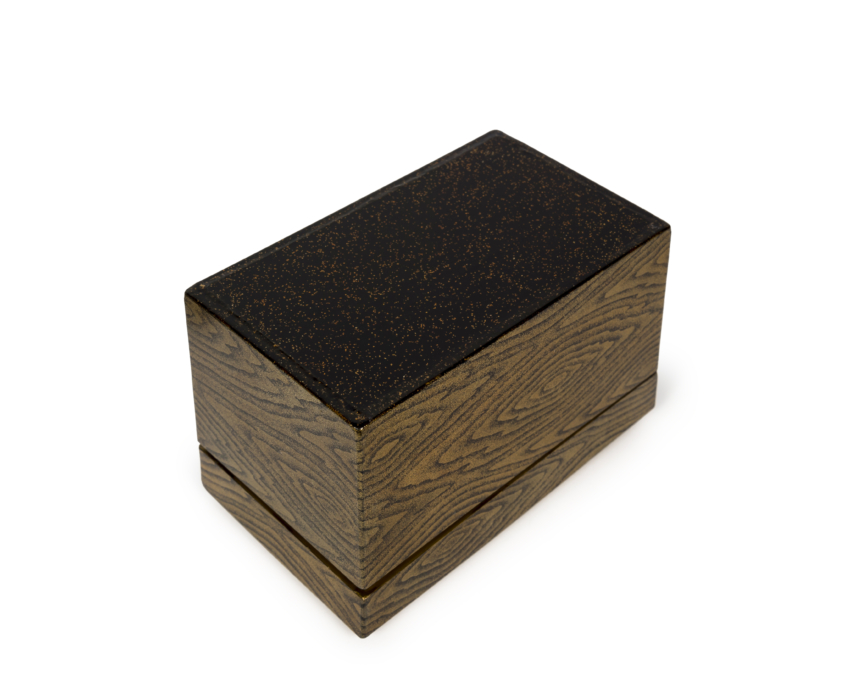

KOBAKO

Référence : 2025-139!

Imposing kobako in nashiji lacquer on a black ground, decorated with a motif imitating wood grain. The lid is adorned with an ikebana basket (hanakago) containing a bouquet of remarkable harmony despite its complexity. The level of detail achieved by the lacquer artist allows several plants in the floral composition to be clearly identified. The chrysanthemum (kiku), first of all, is not only the heraldic emblem of the Japanese imperial family but also a flower with a long and complex history intertwined with that of the archipelago. It was first described by Jacob Breynius in 1689, although the plant owes its name to Carolus Linnaeus: “chrys” in Greek means “golden,” referring to the flower’s original colour, and “anthemon” means “flower”—hence its designation as the “golden flower.”

To understand the symbolism behind the chrysanthemum, one must go back to the years 1500–1400 BC. Chrysanthemums were already cultivated in China as an aromatic flowering herb and were considered a noble plant endowed with unique powers—so much so that only nobles were permitted to grow them in their gardens. They appear on the finest Chinese porcelains, often painted with great refinement. In China, the chrysanthemum is generally a symbol of nobility. Introduced to Japan only in the 8th century, it was elevated by the emperor to the rank of national symbol and later inspired the imperial seal.

During the Heian period, the imperial family took particular interest in the chrysanthemum, even creating a festival in its honour, held on the 9th day of the 9th month at the Kamigamo Shrine in Kyoto: the annual Chōyō no Sekku, or Chrysanthemum Festival. After the ceremony, priests dressed as white crows perform a ritual dance with bows and arrows, followed by children from the area engaging in sumo bouts within the shrine precincts.

Although long popular throughout Japan, it was not until the 13th century that Emperor Go-Toba adopted the sixteen-petaled chrysanthemum as the formal emblem of the imperial family. Chrysanthemum heraldry represents the emperor, the imperial household, and the Japanese people. It is said that emperors’ thrones were once entirely covered with chrysanthemums, giving rise to the expression “the Chrysanthemum Throne.” Initially reserved for the aristocracy, chrysanthemum cultivation expanded greatly during the Edo period (1600–1868), beginning in Kyoto. Numerous specialists developed and exhibited new varieties in inns and temples, recording each detail—form, colour, name, and price—in dedicated registers. Although centred in Kyoto between 1688 and 1703, chrysanthemum culture eventually spread throughout the country.

The chrysanthemum is also one of the four Junzi, or “gentlemen”: the plum, the orchid, the bamboo, and the chrysanthemum together form the “Four Gentlemen,” each symbolizing a season—winter for the plum, spring for the orchid, summer for bamboo, and autumn for the chrysanthemum. They remain essential motifs in the pictorial arts across East Asia.

This rich symbolism explains the recurrence of the chrysanthemum in many contexts—on the Japanese passport, on 50-yen coins, and in the Supreme Order of the Chrysanthemum, the highest distinction a Japanese citizen can receive from the emperor. No other flower in the world is associated with such an honour.

In the Japanese language of flowers, the sunflower (himawari) represents radiance and respect. It symbolizes brilliant beauty and admiration for light and life. The sunflower is also renowned for its fidelity to the sun, turning its head to follow its path throughout the day. This characteristic has given the sunflower a deeper meaning in Japan, where it symbolizes constancy and loyalty—values highly regarded in a culture deeply attached to tradition and hierarchy. By faithfully following the sun, the sunflower becomes a powerful metaphor for these virtues.

Inside the kobako is a lacquered tray decorated with the same wood-grain motif as the exterior. The interior of the lid features a scene of a pavilion beneath an ancient pine tree on the edge of a lake, set within a karst landscape on a gold nashiji ground.

Japan – Meiji period (1868–1912)

Height: 11 cm – Length: 27.5 cm – Width: 10.5 cm

Tray: Height: 2 cm – Length: 9.5 cm – Width: 6 cm