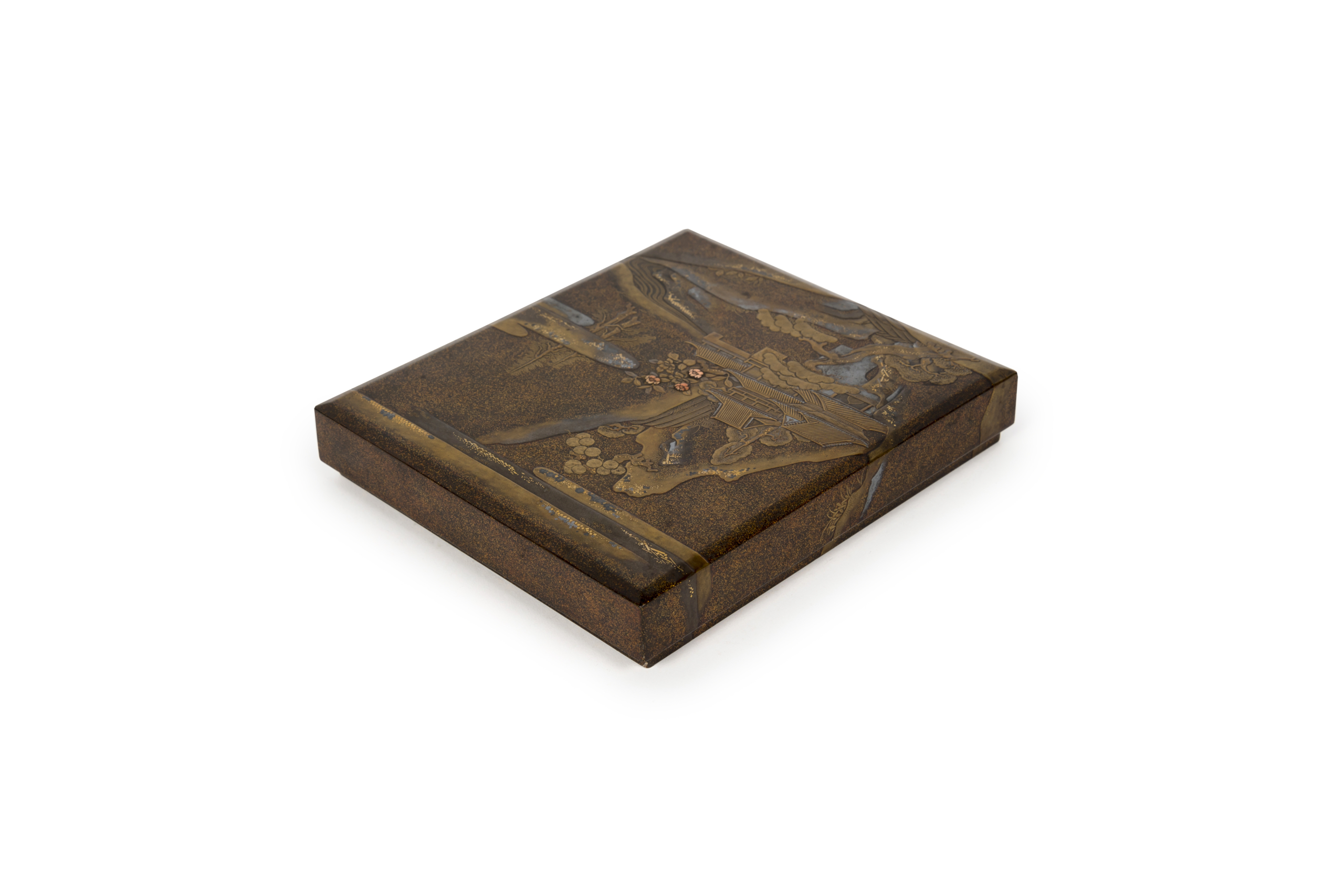

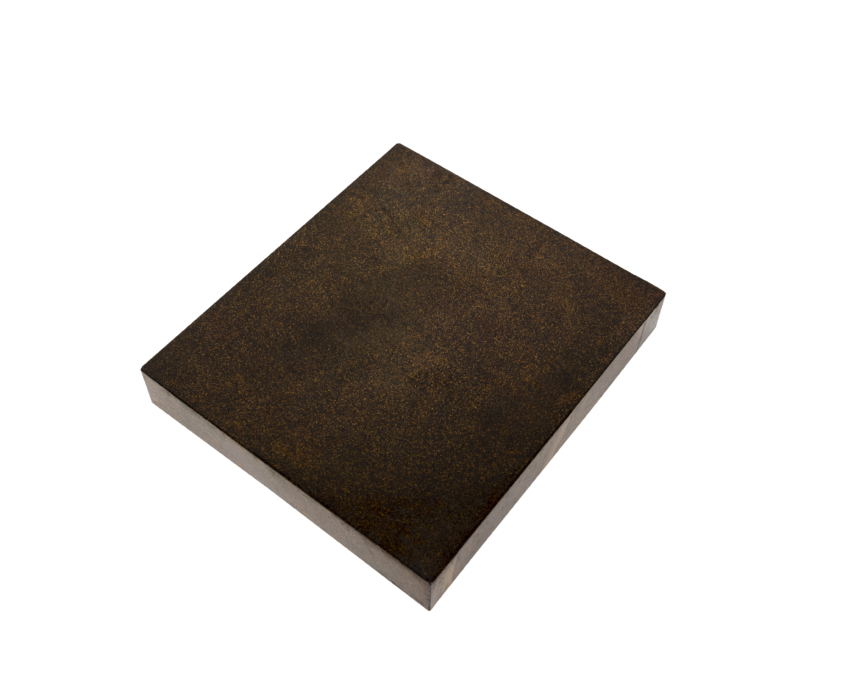

SUZURIBAKO MOUNTAIN PAVILION

Référence : 2025-1380

Suzuribako ou boite à écrire de forme rectangulaire à décor d’une imposante architecture Suzuribako, or writing box, of rectangular shape, decorated with an imposing architecture realized in hira maki-e lacquer, probably a palatial structure, situated beside a waterfall and a mountain river. On its lid alone, this piece combines various lacquer techniques, making it an excellent example of the skill and versatility of lacquer craftsmanship of the end of the Edo period.

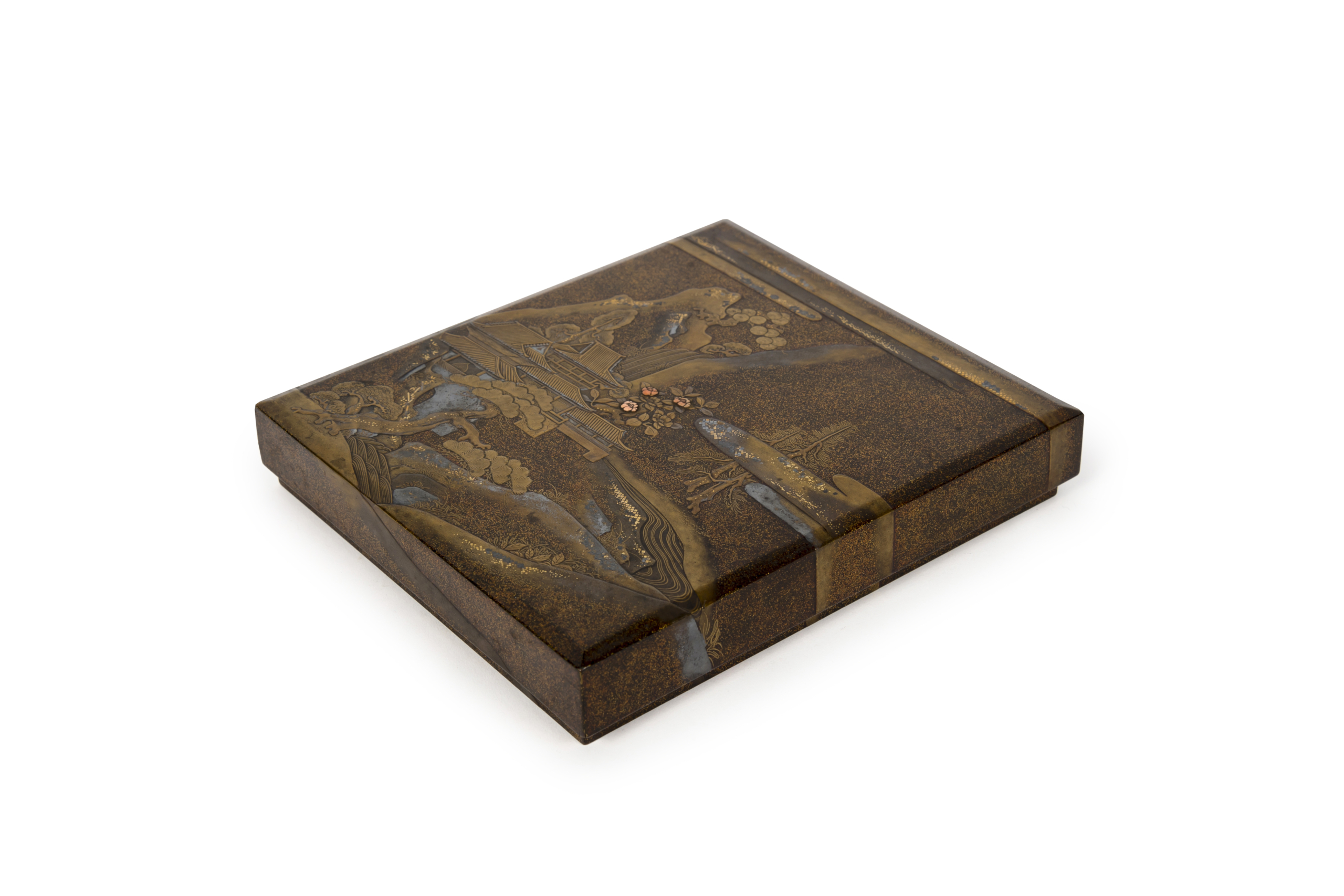

First, a nashiji background is applied across the entire piece—this technique involves sprinkling fine metallic powder, variably composed of gold and silver, into fresh lacquer. Afterward, multiple layers are added to build up the design, each one interspersed with drying and polishing stages to ensure a perfectly smooth texture. With the takamaki-e technique, volume is created using charcoal or clay, which is then lacquered to produce striking height differences in the composition, adding a sense of realism.

The decor extends over the entire box, from the lid to each side, and includes a subtle variety of techniques—from the use of kirigane across the surface to the application of raden to highlight a specific detail. In the former, countless gold flakes of varying sizes and shapes are used to suggest the grainy texture of karstic rock and the bark of pine and cedar trees. Higher up, the same technique, this time with a predominance of silver and tin, is used to convey the heaviness of clouds, becoming omnipresent in the upper register.

Finally, the raden technique is used three times to depict peach blossoms, crafted from angel skin coral. The peach tree holds a unique symbolic meaning in Japan. It is widely celebrated during the annual Hanami festival, where people gather to admire and celebrate the beauty of cherry and peach blossoms. The “momo” flower marks the arrival of spring and symbolizes renewal, youth, and purity. Like the cherry blossom, it is often used to represent the fleeting nature of life, embodied by the transient beauty of nature.

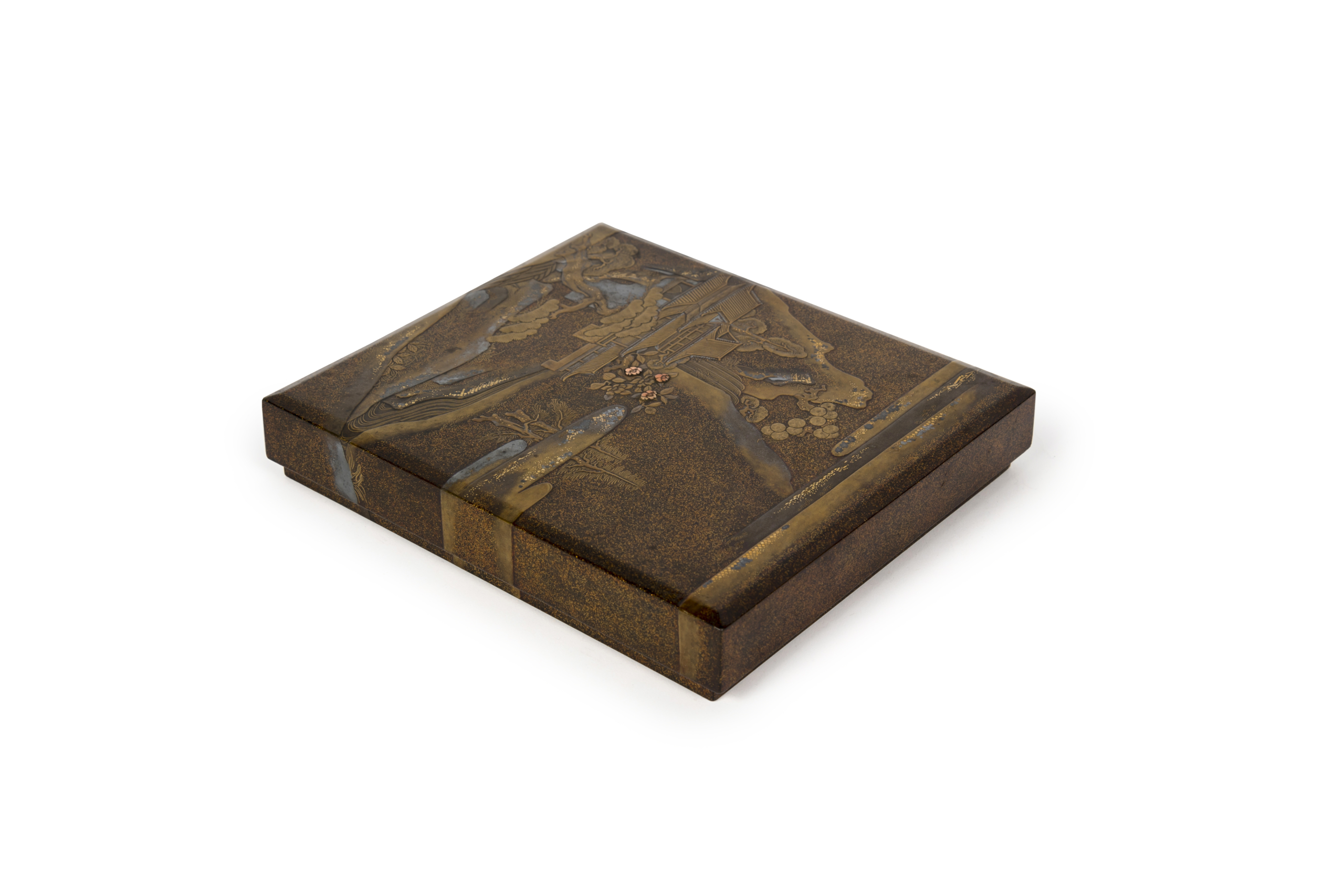

The scene does not simply portray fishermen’s or farmers’ homes. Rather, the quality of the decoration is evident in the harmony of the composition. The two houses are depicted with great realism—you can see the grain of the wood used for the siding, the strands of rice straw that make up the thatched roofs, and even the noren (a traditional Japanese doorway curtain) appears slightly parted, suggesting a welcoming gesture.

On either side of this architecture, various trees with rich symbolism are represented:

The willow (Salix japonica), placed between the two houses, is known for its ability to thrive in harsh conditions. Its deep roots can absorb water and nutrients from the soil. This resilience and vitality are seen as qualities that promote physical and emotional healing. In Japanese folklore, sitting under a willow tree is believed to bring good fortune and rejuvenate both body and spirit. The willow’s slender, delicate branches also embody the aesthetics of wabi-sabi, a Japanese philosophy that finds beauty in imperfection and transience.

The cedar, or sugi in Japanese, is a revered tree. It is often planted around temples and shrines, either symbolizing protection and purification or for practical reasons, as cedar is a prized building material in Japan. In Japanese mythology, the cedar is seen as a link between the earthly and the divine. Its presence is said to ward off evil spirits and bring prosperity and luck.

The pine, or matsu, is another deeply symbolic tree. Its remarkable longevity and resistance to harsh weather make it a symbol of strength and perseverance. Pines are also commonly planted near temples and shrines to represent protection and wisdom. Their distinctive, twisted branches evoke the beauty of imperfection and the ability to overcome life’s obstacles.

The cherry tree, or sakura, is arguably Japan’s most iconic tree. Like the peach, it is celebrated during Hanami. Its spectacular blossoming is seen as a symbol of fleeting beauty and renewal. The Japanese see a life lesson in this fragility—beauty is transient, so it must be appreciated while it lasts.

Although barely visible behind the house in the foreground, two more cherry trees appear in the second register, clinging precariously to the karstic rock of a misty mountain. In the upper register, a full moon can be discerned, rendered with a masterful blend of metallic oxides—whose precise formula remains the secret of lacquer masters. It appears to reflect off the rocks and clouds, echoing the gold, silver, and tin clouds that envelop the volumes, suggesting the thick mist that surrounds riverbanks in early spring.

The extraordinary urushi maki-e work is evident in the wide array of lacquer techniques used in harmony with the subject’s deep symbolic value. For all these reasons, this unique piece stands as a remarkable example of the technical mastery, craftsmanship, and near-naturalist artistic sensitivity of Japanese artisans from the late Edo period.

Japan – Edo (1603-1868)

Length: 22.5 cm – Width: 20 cm – Height: 4.5 cm